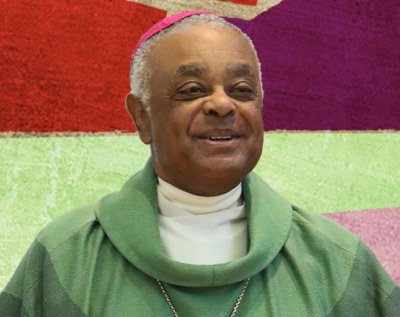

Abp. Wilton Gregory has track record of trying to evade justice

Uncovering the Cover-Up

In spite of holding himself forth as a champion of victims, Abp. Wilton Gregory’s track record reveals instead lack of transparency and obfuscation, and Catholics are waiting to see what Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr will uncover in his newly launched investigation of both the Atlanta and Savannah dioceses.

Observers suggest Carr is likely to unearth many long-buried abuse cases, particularly in Atlanta, where Gregory is wrapping up a 14-year stint as archbishop, before moving on to head the Washington, D.C. archdiocese.

According to the narrative Gregory and his allies have constructed over the past two decades, the archbishop is a strong victims’ advocate dedicated to stamping out clerical sex abuse. But a closer look at his record reveals a different story.

In 2004, Gregory, then bishop of Belleville, Illinois, was held in contempt of court for refusing to release records related to a sex abuse case involving a retired priest.

In 2004, Bp. Gregory was held in contempt of court for refusing to release records related to a sex abuse case.

As archbishop of Atlanta, for years Gregory refused requests by victims’ advocacy groups to release the names of credibly accused clergy.

Last November he relented, issuing a list of 15 predator priests. But the timing of the release — in the wake of the Theodore McCarrick scandal — was not lost on victims or their advocates, many of whom denounced Gregory’s move as a cynical attempt at self-preservation, designed to deflect attention from his close relationship with McCarrick.

Another red flag: Abp. Gregory’s list identified only 15 predator priests. Two days after the Atlanta clergy were named, Savannah Bp. Gregory Hartmayer identified 16 predator priests from his southern Georgia diocese.

This prompted a still-unanswered question: How could the diocese of Savannah, home to just 85,000 Catholics, have more predators than the archdiocese of Atlanta, home to 1.2 million Catholics?

Gregory’s critics point to other blots on his record. In 2015, victims’ advocacy group SNAP published the names of six predator priests who had victimized minors in other states and spent time in Atlanta. Though allegations against the men attracted media coverage in other states, in Georgia, they remained under the radar.

If the archbishop was truly concerned about clerical sex abuse victims, it was asked, why didn’t he publicize the men’s identities? Each was either credibly accused of or had admitted to sexual abuse of minors. Identifying them could have encouraged any Atlanta victims to step forward to claim justice.

In December, abuse victim “Phillip Doe” filed suit against Gregory and the Atlanta archdiocese, claiming they have “conspired, continue to conspire, and have actively engaged in efforts to” conceal clerical sex abuse.

In spring 2018, Abp. Gregory successfully undermined the Hidden Predators’ Act, a Georgia bill that would have extended the statute of limitations from age 23 to 38 and allowed victims to sue their alleged abusers as well as institutions that enabled the abuse.

To many, Gregory’s lobbying — occurring just three months before the McCarrick revelations broke — was the final proof that the archbishop doesn’t fight for clerical sex abuse victims, as he claims, but against them.