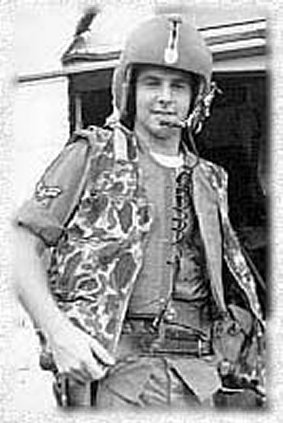

Rank and organization: Airman First Class, U.S. Air Force

Detachment 6, 38th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron, Bien Hoa Air Base, Republic of Vietnam.

Place and Date: Near Cam My, 11 April 1966.

Pitsenbarger loved the Air Force and his job, which was to save lives. His commander, Maj. Maurice Kessler, called him “One of a special breed. Alert and always ready to go on any mission.” Another rescue pilot, Capt. Dale Potter, said Pits was a “young eager kid who was always ready to go, and always willing to get into the thick of the action where he could be the most useful.”

Although Pitsenbarger didn’t escape that hellhole alive, nine other men did, thanks to the courage and devotion to duty of a 21-year-old airman, a former supermarket stockboy from Piqua, Ohio. For his bravery, the Air Force awarded Bill Pitsenbarger its second highest award — the Air Force Cross, becoming the first enlisted airman to receive the medal.

“Bill was an ordinary guy with extraordinary courage and determination,” said William, his father. “I’m very proud of him. And I’d like to think if you took any PJ in the Air Force and put him in the same situation, they’d do the same thing. They’re special people.”

And they live by a special code, one that often demands they risk everything, pledging “These Things We Do That Others May Live.”

Airman 1st Class William H. Pitsenbarger

A1C – E4 – Air Force – Regular

21 year old – Single

Born on July 08, 1944

From PIQUA, OHIO

On April 11th, 1966, 21-year old A1C William H. Pitsenbarger of Piqua, Ohio was killed while defending some of his wounded comrades. For his bravery and sacrifice, he was posthumously awarded the nation’s second highest military decoration, the Air Force Cross.

“Pits”, as he was known to his friends, was nearing his 300th combat mission on that fateful day when some men of the U.S. Army’s 1st Division were ambushed and pinned down in an area about 45 miles east of Saigon. Two HH-43 “Huskie” helicopters of the USAF’s 38th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron were rushed to the scene to lift out the wounded. Pits was a pararescueman (PJ) on one of them. Upon reaching the site of the ambush, Pits was lowered through the trees to the ground where he attended to the wounded before having them lifted to the helicopter by cable.

After six wounded men had been flown to an aid station, the two USAF helicopters returned for their second loads. As one of them lowered its litter basket to Pitsenbarger, who had remained on the ground with the 20 infantrymen still alive, it was hit by a burst of enemy small-arms fire. When its engine began to lose power, the pilot realized he had to get the Huskie away from the area as soon as possible. Instead of climbing into the litter basket so he could leave with the helicopter, Pits elected to remain with the Army troops under enemy attack and he gave a “wave-off” to the helicopter which flew away to safety.

Pits continued to treat the wounded and, when the others began running low on ammunition, he gathered ammo clips from the dead and distributed them to those still alive. Then, he joined the others with a rifle to hold off the Viet Cong. About 7:30 PM that evening, Bill Pitsenbarger was killed by Viet Cong snipers. When his body was recovered the next day, one hand still held a rifle and the other a medical kit.

.

‘That Others May Live’

By John L. Frisbee, Contributing Editor

October, 1983

By April 1966, 21-year-old A1C William H. Pitsenbarger, then in the final months of his enlistment, had seen more action than many a 30-year veteran. Young Pitsenbarger had gone through long and arduous training for duty as a pararescue medic with the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service and had completed more than 300 rescue missions in Vietnam, many of them under heavy enemy fire. He wore the Air Medal with five oak leaf clusters; recommendations for four more were pending. A few days earlier, he had ridden a chopper winch line into a minefield to save a wounded ARVN soldier.

His service with ARRS convinced Pitsenbarger that he wanted a career as a medical technician. He had applied to Arizona State University for admission in the fall. But that was months away. He had a job to do in Vietnam and, as rescue pilot Capt. Dale Potter said, Pitsenbarger “was always willing to get into the thick of the action where he could be the most help.”

On April 11 at 3 p.m., while Pitsenbarger was off duty, a call for help came into his unit, Detachment 6, 38th ARR Squadron at Bien Hoa. Elements of the Army’s 1st Infantry Division were surrounded by enemy forces near Cam My, a few miles east of Saigon, in thick jungle with the tree canopies reaching up to 150 feet. The only way to get the wounded out was with hoist-equipped helicopters. Pitsenbarger asked to go with one of the two HH-43 Huskies scrambled on this hazardous mission.

Half an hour later, both choppers found an area where they could hover and lower a winch line to the surrounded troops. Pitsenbarger volunteered to go down the line, administer emergency treatment to the most seriously wounded, and explain how to use the Stokes litter that would hoist casualties up to the chopper.

It was standard procedure for a pararescue medic to stay down only long enough to organize the rescue effort. Pitsenbarger decided, on his own, to remain with the wounded. In the next hour and a half, the HH-43s came in five times, evacuating nine wounded soldiers. On the sixth attempt, Pitsenbarger’s Huskie was hit hard, forced to cut the hoist line, and pull out for an emergency landing at the nearest strip. Intense enemy fire and friendly artillery called in by the Army made it impossible for the second chopper to return.

Heavy automatic weapons and mortar fire was coming in on the Army defenders from all sides while Pitsenbarger continued to care for the wounded. In case one of the Huskies made it in again, he climbed a tree to recover the Stokes litter that his pilot had jettisoned. When the C Company commander, the unit Pitsenbarger was with, decided to move to another area, Pitsenbarger cut saplings to make stretchers for the wounded. As they started to move out, the company was attacked and overrun by a large enemy formation.

By this time, the few Army troops able to return fire were running out of ammunition. Pitsenbarger gave his pistol to a soldier who was unable to hold a rifle. With complete disregard for his own safety, he scrambled around the defended area, collecting rifles and ammunition from the dead and distributing them to the men still able to fight.

It had been about two hours since the HH-43s were driven off. Pitsenbarger had done all he could to treat the wounded, prepare for a retreat to safer ground, and rearm his Army comrades. He then gathered several magazines of ammunition, lay down beside wounded Army Sgt. Fred Navarro, one of the C Company survivors who later described Pitsenbarger’s heroic actions, and began firing at the enemy. Fifteen minutes later, as an eerie darkness fell beneath the triple-canopy jungle, Pitsenbarger was hit and mortally wounded. The next morning, when Army reinforcements reached the C Company survivors, a helicopter crew brought Pitsenbarger’s body out of the jungle. Of the 180 men with whom he fought his last battle, only 14 were uninjured.

William H. Pitsenbarger was the first airman to be awarded the Air Force Cross posthumously. The Air Force Sergeants Association presents an annual award for valor in his honor.

The Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service is legendary for heroism in peace and war. No one better exemplifies its motto, “That Others May Live,” than Bill Pitsenbarger. He descended voluntarily into the hell of a jungle firefight with valor as his only shield–and valor was his epitaph.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Citation:

Airman First Class Pitsenbarger distinguished himself by extreme valor on 11 April 1966 near Cam My, Republic of Vietnam, while assigned as a Pararescue Crew Member, Detachment 6, 38th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron. On that date, Airman Pitsenbarger was aboard a rescue helicopter responding to a call for evacuation of casualties incurred in an on-going firefight between elements of the United States Army’s 1st Infantry Division and a sizable enemy force approximately 35 miles east of Saigon. With complete disregard for personal safety, Airman Pitsenbarger volunteered to ride a hoist more than one hundred feet through the jungle, to the ground. On the ground, he organized and coordinated rescue efforts, cared for the wounded, prepared casualties for evacuation, and insured that the recovery operation continued in a smooth and orderly fashion. Through his personal efforts, the evacuation of the wounded was greatly expedited. As each of the nine casualties evacuated that day were recovered, Pitsenbarger refused evacuation in order to get one more wounded soldier to safety. After several pick-ups, one of the two rescue helicopters involved in the evacuation was struck by heavy enemy ground fire and was forced to leave the scene for an emergency landing. Airman Pitsenbarger stayed behind, on the ground, to perform medical duties. Shortly thereafter, the area came under sniper and mortar fire. During a subsequent attempt to evacuate the site, American forces came under heavy assault by a large Viet Cong force. When the enemy launched the assault, the evacuation was called off and Airman Pitsenbarger took up arms with the besieged infantrymen. He courageously resisted the enemy, braving intense gunfire to gather and distribute vital ammunition to American defenders. As the battle raged on, he repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire to care for the wounded, pull them out of the line of fire, and return fire whenever he could, during which time, he was wounded three times. Despite his wounds, he valiantly fought on, simultaneously treating as many wounded as possible. In the vicious fighting which followed, the American forces suffered 80 percent casualties as their perimeter was breached, and airman Pitsenbarger was finally fatally wounded. Airman Pitsenbarger exposed himself to almost certain death by staying on the ground, and perished while saving the lives of wounded infantrymen. His bravery and determination exemplify the highest professional standards and traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Air Force.

.

KAMAN HH-43B “HUSKIE”

The “Huskie” was used primarily for crash rescue and aircraft fire-fighting. It was in use with the U.S. Navy when delivery of the H-43As to the USAF Tactical Air Command began in November 1958. Delivery of the -B series began in June 1959. In mid-1962, the USAF changed the H-43 designation to HH-43 to reflect the aircraft’s rescue role. The final USAF version was the HH-43F with engine modifications for improved performance. Some -Fs were used in Southeast Asia as “aerial fire trucks” and for rescuing downed airmen in North and South Vietnam. Huskies were also flown by other nations including Iran, Colombia, and Morocco.

A Huskie on rescue alert could be airborne in approximately one minute. It carried two rescuemen/fire-fighters and a fire suppression kit hanging beneath it. It often reached crashed airplanes before ground vehicles arrived. Foam from the kit plus the powerful downwash air from the rotors were used to open a path to trapped crash victims to permit their rescue.

The HH-43B on display, one of approximately 175 -Bs purchased by the USAF, established seven world records in 1961-62 for helicopters in its class for rate of climb, altitude and distance traveled. It was assigned to rescue duty with Detachment 3, 42nd Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron, Kirtland AFB, New Mexico, prior to its retirement and flight to the Museum in April 1973.

Wild Thing’s comment……..

All those that have served our country touch all of our lives. It is because of each one of them that we are able to have lived in the land of the free, a freedom that we have had unlike other countries. Ours was the best, our Freedom and we owe each day of that to our Veterans and to men that have served like Airman First Class William Hart Pitsenbarger.

I wish there was a way to thank each one for their sacrifice, but I know one thing, they will NEVER be forgotten, NEVER!

.

….Thank you Mark for sending this to me.

….Thank you Mark for sending this to me.

Mark

3rd Mar.Div. 1st Battalion 9th Marine Regiment

1/9 Marines aka The Walking Dead

VN 66-67

.

Thanks so much for this great story. This is a perfect example of courage. You are right Chrissie…I will not forget nor allow others to do so.

Never forget the Pentagon pimps tied our warriors hands behind their backs with OFF LIMITS bombing targets and RULES OF NON-ENGAGEMENT…Until President Nixon commenced with B-52 Linebacker I andII ops over Hanoi!

Thank you for posting this Chrissie and Mark. The unsung heroes of battle are the ones who risk it all to save their brothers on the battlefield. A1C William H. Pitsenbarger is an outstanding example. Another was the steel nerve and will of Maj. Ed Freeman and Lt. Col. Bruce Crandall, pilots who put men like Pitsenbarger on the scene. Quite different than from engaging at 30,000 ft or flybys at Mach 1 they all stayed in the hot zone until one of three things happen. They succeed, they fail or they are driven off. Thank God Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and Osama Obama were not presidents back then, those casualties may never have been recovered.

Where are the recipients of that medal in the current wars?

First time I have heard this story. Airman Pitsenbarger really believed in his mission. He risked it all for fellow Americans. Surprisingly this is not unusual on the battlefield. It is just not often recognized.

Thank you everyone for your wonderful comments.

((( hug )))

Chrissie

I found this the other day and his heroism and due honor had been delayed. According to the family inter-service politics. I don’t know, I thought this was a very inspiring story. When considering todays entitlement society. However, when you read some of these stories from Iraq, like that of Paul Ray Smith are just as selfless as the ones we have seen or heard.